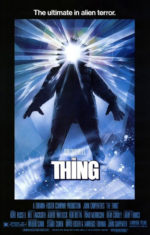

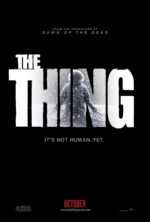

A horror thriller set in the frigid and isolated American Research Facility in Antarctica, John Carpenter’s The Thing plants a truly nightmarish alien—which can perfectly mimic any living being—into the middle of a tight-knit crew of twelve men. After witnessing some bone-crunchingly gruesome deaths at the tentacles of this invulnerable, shape-shifting alien, the men grow paranoid and turn on each other, fearing that any one of them could be an imposter.

The Thing opens with a sparse, tense soundtrack as a Norwegian helicopter crew tries to shoot a sled dog fleeing through the desolate, deep snowfields. Right from the start, things seem wrong as this poor animal is mercilessly hunted—and when it finds shelter with the Americans, things turn bad fast. Traveling to the frozen and burnt-out shell of the Norwegian camp, the U.S. team finds the remains of a life or death battle where death won. Barricaded deep inside the camp they find the frozen body of a man who slit his own throat rather than face his opponent, and outside, they find the charred remains of a grotesque corpse that looks like several bodies melted together. But this is just the appetizer, the alien infects and picks off the U.S. crew with some of the most visceral and surreal shape-shifting you’ll ever see.

The Thing remains a groundbreaking creature effects film to this day. In the days before digital effects, director John Carpenter set out to make a monster movie but didn’t want a ‘guy in a rubber suit.’ Seeking something truly inhuman, he collaborated with the twenty-year-old effects wizard Rob Bottin, who had created the revolutionary werewolf transformations in The Howling. Bottin’s concept was that the alien was a collection of every life form it had ever touched, and he worked seven days a week for over year to create the creature effects for the film.

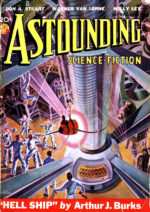

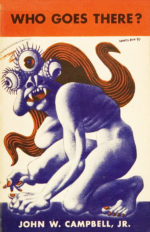

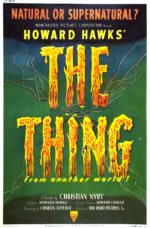

Carpenter was inspired by the 1951 film, The Thing from Another World, but his film more closely follows John W. Campbell Jr.’s short novel, Who Goes There?, on which both films are based. With financial backing from Universal Pictures, the film had a budget for six soundstages with refrigeration, so the actors’ breath would be visible in the freezing scenes (which happened to be filmed during a heat wave in Los Angeles) and the entire exterior of the Research Facility was built on location in British Columbia. Construction took place during the summer, so the set was naturally buried in snow and ice when the exteriors were filmed in the winter. The cast and crew bonded during the uncomfortable winter shooting and braved dangerous trips from their sleeping quarters up the winding and icy road to the Research Facility set.

The film did not do as well as was hoped at the box office; opening against the 1982 blockbuster hits E.T.: the Extraterrestrial and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Battling this tough competition, the films The Thing and Blade Runner tanked at the box office, but gained respect and popularity through rereleases and home video. Actor Charles Hallahan said in an interview that wherever he travels someone always asks him about his very memorable death scene from The Thing. And every winter at the South Pole, after the last flight until spring, the crew of the U.S. South Pole Station watches a double feature of The Shining and The Thing.

Enjoying the site? If so consider supporting it with alien-infused caffeine…

‘Alaskan’ sled dog???

Presumably the reason they kept all those dogs in the first place was to use them as sled dogs.

And technically, “Jed,” the animal actor, was part wolf and part Alaskan Malamute, so it is not that out of line. Also: Wikipedia Article on Sled Dogs

And if you’re really geeky about dogs — here is a fan page about Jed the dog from The Thing