At its heart, WALL·E is a simple and charming love story between two mismatched robots. But it is also a space adventure that sweeps a little robot off the trash-filled and abandoned planet Earth and onto a distant high-tech spaceship in pursuit of his sweetheart—oh, and, on the way, he helps uncover a secret that may hold the key to redeeming humankind.

On a future Earth, buried in trash and covered in a dull haze of dirt and grime, humans long ago escaped to space, leaving behind an army of robots to clean up their mess. Centuries later, a single small trash compacting robot, WALL·E, survives, still dutifully stacking compressed cubes of garbage and borrowing spare parts from his long-dead fellow compacting units. He’s curious, kind and makes the most of his life by collecting trinkets from the rubbish.

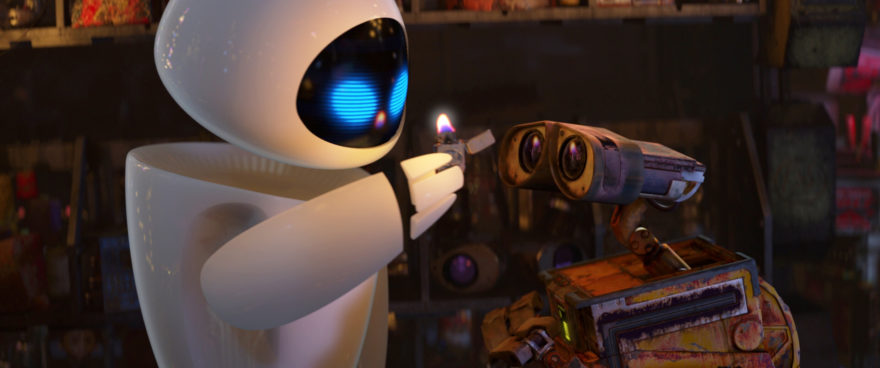

Into this routine a new probe unit arrives—sleek, modern and on a mission to find biological life on Earth. Instantly smitten, the little robot follows the probe back to her home: the distant, luxurious space ship where Earthlings long ago made a new home and lost touch with their roots on that third planet from the sun.

The ninth animated feature film from Pixar, WALL·E was a film that took big risks. Director Andrew Stanton created a compelling story without much dialogue. He explained that, “all the other elements… the lighting, the acting, the music and what the camera’s telling you, they have to fill in that hole.” Looking to past masters for inspiration, his team studied the films of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and even Harold Lloyd—great silent filmmakers who told stories without spoken words. In fact, the WALL·E character was based, in part, on the lovable “stone-faced, sad eyed” silent star Buster Keaton.

The director also obsessed about creating a completely believable look for the film. Not only did he steer clear of anything that looked remotely like ‘computer graphics,’ he copied the actual imperfections of the 1970s Panavision movie cameras—down to the way the image shifts when changing focus, and how the weight of the camera feels as it moves. Unsatisfied with the computer-generated tests, they rented a real movie camera and filmed life-sized mock-ups of Eve and WALL·E. From this, they discovered errors in the programs used to simulate the camera lenses and upgraded the software so it matched reality.

The film is littered with obvious—and obscure—references to science fiction classics, including the glowing red eye of HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey, a stray piece of shrapnel modeled directly from Aliens and, honoring Sigourney Weaver’s roles in both the Alien franchise and Galaxy Quest, her voice is featured as that of the ship’s computer.

WALL·E was number one at the box office upon its release. It played in theaters for seven months and earned over $500 million worldwide. The critics, including Roger Ebert, raved and The Hollywood Reporter ventured that it was Pixar’s most original film to date (still true, BTW). Filmmaker Terry Gilliam, director of 12 Monkeys and Brazil, found the film “a stunning piece of work.” WALL·E won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature, was nominated for five additional Oscars and won the coveted Hugo award—as well as winning dozens of other prestigious awards. In 2010 it topped Time’s list of the best films of the decade.

Enjoying the site? If so consider supporting it with alien-infused caffeine…